Hard Work, Plain Meals, and the Women Who Endured

By the time the textile factory whistle blew at dawn in Calais, Maine, Bridget Finerty (you can officially “meet” Bridget in this post: “A Canadian Named Bridget”) was likely awake, her fingers stiff with cold and her stomach hollow from sleep. Like thousands of other immigrant women working the textile mills of New England in the 1860s, Brigit’s days were measured in looms and lunch breaks, not hours.

Despite my research, I’ve never been unable to uncover whether or not Bridget and her family rented a home in Calais from a landlord or from a mill owner, though research seems to suggest that the majority of mill workers and their families tended to utilize mill housing when available. It’s safe to assume twenty-something-year-old Bridget would have lived close enough to the mill to hear the early morning whistles, rousing her to work.

The demands of millwork—long, grueling shifts in lint-choked air—dictated not only her time but her appetite. Food wasn’t a pleasure or pastime; it was fuel, plain and portable, shaped by necessity and whatever provisions she could afford or prepare in haste. To understand Bridget’s life in those years is to understand what she ate, when she ate, and how the factory floor shaped the flavor of her days.

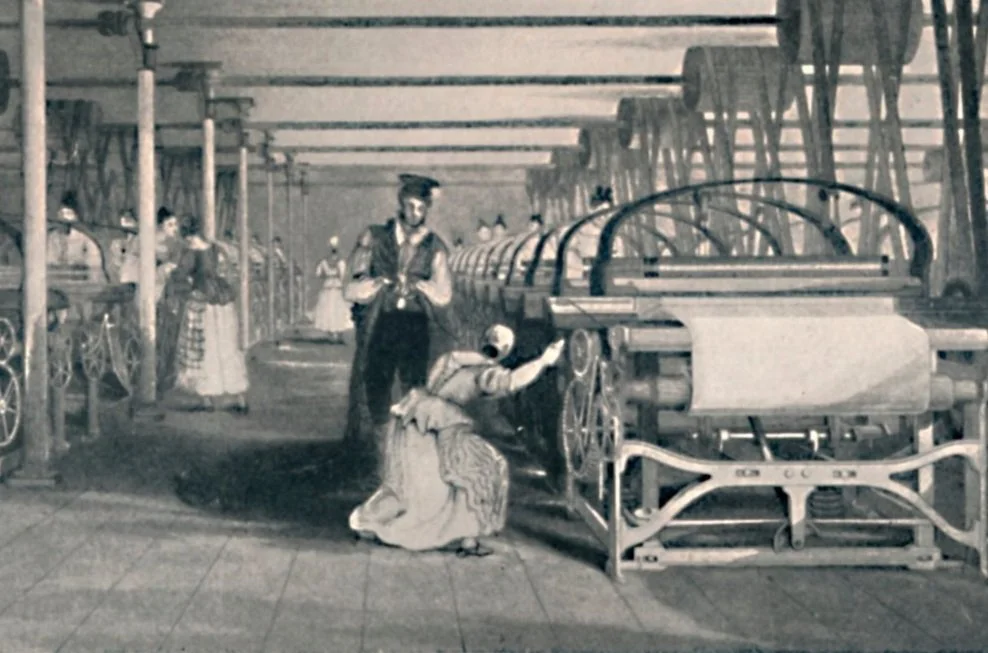

Inside the mill, Bridget stood for twelve hours a day at the power loom, the clatter of machines so loud she probably learned to communicate in gestures, not words. It’s safe to say she likely worked among rows of other women and girls, each one stationed at a power loom—massive, rhythmic machines fed by belts and pulleys spinning from the mill’s central waterwheel.

Weaving by Power Looms, 1835, 1904 by Unbekannt.

Her hands were never still: rethreading snapped threads, replacing spent bobbins, tugging at warped cloth. Fine cotton fibers floated in the humid air, coating her throat and clinging to her lashes. By mid-morning, she was already flushed from the heat of the machinery and the pressure to keep up with the endless motion of cloth. There was no leisurely lunch, no break room—just a bell signaling thirty minutes to eat whatever she had tucked into her apron pocket or wrapped in cloth at the edge of the room. Work didn’t pause for hunger, and meals had to be quick, cheap, and sustaining enough to carry her through the afternoon stretch.

Most days, Bridget’s midday meal might be plain and practical: a slice of coarse brown bread spread with lard or drippings, maybe a wedge of cheese if she could spare the cost. Sometimes she could have brought a cold potato from the night before, wrapped in cloth and salted to give it flavor. Tea, when she could get it, was sipped lukewarm from a tin cup; sugar was a luxury.

These were foods that traveled well, needed no reheating, and could be eaten quickly with callused fingers. Her diet was a blend of Irish frugality learned from her immigrant parents Patrick and Annie and New England necessity—root vegetables, salt pork, oats, and day-old bread—whatever she or the women in her boarding house could stretch from the week’s wages. (Typically between $3.00 and $3.50, according to preliminary research. Not a lot, but more than women typically earned on local farms or other rural occupations)

The industrial grind left little room for nostalgia, but even in the humblest bites, perhaps echoes of home remained: the comfort of boiled cabbage, the memory of soda bread, the ritual of strong tea when the day finally ended.

It’s easy to romanticize the past, to imagine Bridget’s work apron as quaint or her bread as artisanal—but there was nothing curated about survival. Her meals were shaped by exhaustion, budget, and the buzz of machines that left little time to chew, let alone savor.

That mindset—food as fuel, not pleasure—slunk its way down the family tree, passed in quiet habits more than recipes.

And yet, there’s something enduring in that instinct to make do, to find nourishment in scraps and routine. When I sift flour or boil a potato with salt, I’m not recreating her life—I’m attempting to imagine what could have been the shape of it. The work she did, the food she ate, and the strength it must have taken to endure all: alive, not just in my genealogy notes, but in my kitchen.

Her story isn’t just about who she was—it’s about what fed her, and how, in quiet ways, that same practicality has lingered in the kitchens of her descendants (the women in my family), shaping our meals more as necessity than ritual.

I’d often lament the fact that our family tree didn’t have a Sunday-sauce Nonna in the kitchen each week, passing down family memories through taste and recipes. I felt cheated and a little lost until this project really had me dig into the roots of who we are as a lineage.

Where did we come from? Why didn’t we focus on recipes and the hearths of our homes quite like other families and backgrounds did?

It’s through researching Bridget that the answer is just starting to form--food was fuel. Food kept us moving forward through very lean, very trying times. It was a means, not a memory, and love it or hate it, it’s who Bridget was, who my grandmother was, who my mother was, and for the majority of my life, who I was.

For more information about the historic mills of Maine, visit these resources: Milltown Maine and the Maine Memory Network.